5 FAQs About Phonological And Phonemic Awareness

May 15, 2022In this post I'll be answering 5 of the most frequently asked questions I received after my previous post titled, ‘What is Phonological Awareness and why does it matter?

Let's dive right in:

1. Is phonological awareness a concept only junior teachers need to be aware of?

No.

Phonological awareness is required by all readers- irrespective of their age. Therefore, it’s important for teachers of all year levels to learn about the continuum of skills and be conscious of their impact on a person's reading ability.

This is especially true for students who may be struggling with reading in middle-upper primary. When teachers are aware of the continuum of phonological skills, they can consider it when implementing any interventions for these readers.

2. How does phonological awareness develop?

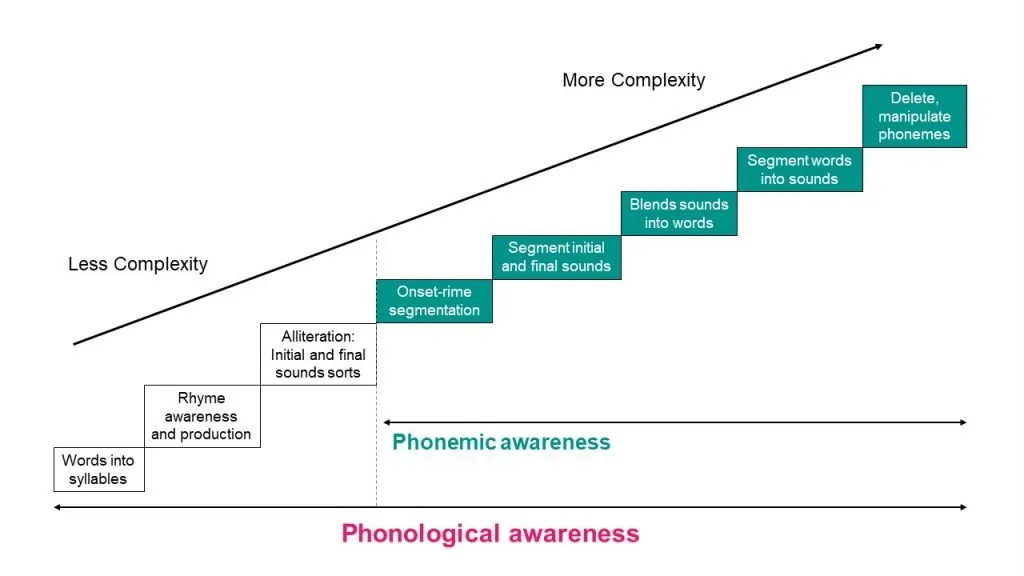

I've found Shuele and Boudreau’s (2008) Sequence of Phonological Awareness Instruction and Intervention diagram a useful resource for visualising the continuum of skills a beginning reader goes through when developing their phonological and phonemic awareness.

A couple of notes about this graphic:

- Students aren’t required to master one step before moving on to the next, however it’s important to understand that each step increases in its level of complexity. E.g. Blending sounds into words (the skill used in decoding) is less cognitively challenging than segmenting words into sounds (the skill used in encoding/spelling).

- Knowledge of this continuum allows you to better pinpoint your students’ current skills and identify possible areas for instruction and differentiation.

3. How much instructional time should be focused on the earlier phonological awareness skills versus specific phonemic awareness skills?

There is some contention in the research about how much instructional time should be spent on developing students’ phonological skills vs phonemic skills.

Some researchers suggests time spent in the earlier phases of phonological awareness is time well spent, whereas others suggests teachers should move through these earlier phases quickly, in order to spend more time focusing on developing their students' skills in phonemic awareness.

Take these two studies for example:

- A 1989 study by Bryant et al. (cited in Gillon, 2018) suggested that knowledge of nursery rhymes at 3 years of age was strongly correlated with performance of rhyme detection at 4 years and with phoneme detection at 5 and 6 years.

- A 1998 study by Muter and Snowling (cited in Gillon, 2018) found that early rhyme detection ability (a phonological awareness skill) did not predict reading accuracy ability at 9 years of age, whereas phoneme deletion ability (a phonemic awareness skill) did.

It seems the most common recommendation now is to be aware of all the stairs on Shuele and Boudreau’s staircase, but spend most of your instructional time developing your students' skills in the phonemic awareness end of the diagram (but of course, you should always be guided by your students' needs).

4. How can you assess phonological and phonemic awareness?

There are several pre-made assessments available to help teachers gather information on students’ phonological and phonemic awareness.

When you’re looking at these assessments, I again think it’s important to be aware of each of the stairs on Shuele and Boudreau’s diagram, so you have a deeper awareness of what exactly is being assessed by the tool (and if there are any gaps).

Some useful assessments I’ve used in the past include:

A. Sutherland Phonological Awareness Test (SPAT-R)

This Australian assessment was first published in 1999 and revised in 2003.

It assesses a student’s knowledge of syllables, rhyme detection, rhyme production, blending CVC words, initial and final phoneme identification, segmentation of CVC words, segmentation of blends, phoneme deletion and reading of nonsense words.

Besides the obvious benefits of it being and Australian assessment (no weird phoneme pronunciations or uncommon words), it’s quite user friendly and doesn’t take a lot of time to administer. The questions get progressively more challenging, so you can stop the assessment when it’s obvious the student’s limit has been reached.

Note: The updated version of the manual states that the norms for this assessment were devised over two decades ago so are likely outdated now, but they say the information gained by completing this assessment is still valuable. I’d have to agree; the strength in this assessment isn’t the score you get at the end, it’s the information you gather along the way.

You can learn more about this assessment here.

B. Heidi Mesmer’s Phonological Awareness Assessment

This assessment was featured in Mesmer’s latest publication, Alphabetics for Emerging Learners (2022).

It assesses rhyme recognition and production, initial and final phoneme identification, blending and segmenting. There are 4 short questions for each area, and they’re very quick to go through.

You can purchase Heidi Mesmer’s book here.

C. David Kilpatrick’s Phonological Awareness Screening Test (PAST)

This assessment was developed in 2003 and comes in four different version (so you can redo the test several times throughout the year).

I like the flexibility in administration of this one- especially for students beyond Foundation- as it allows students to start part way through the assessment, so they don’t have to go through all the easier items if it’s not required.

As with the SPAT-R, you discontinue administering the test once it becomes too challenging.

The only issue I found with this assessment was that the first questions around syllables were a bit challenging for some EAL Foundation students (e.g. "say sunset but don't say sun") and it meant some of them lost their confidence right at the start. For this reason, I think it would be probably be best used in late Foundation onwards.

You can purchase David Kilpatrick’s book here.

5. How can you build students’ phonemic awareness?

Remember, phonemic awareness is all about hearing the sounds within words, so any activity you do that focuses on those sounds (identification, manipulation and deletion) can help to build a child’s phonemic awareness.

A couple of quick and easy activities/ games include:

Silly Rhymes

I once worked with a teacher who used to teach all her students a silly song that they all loved. It didn’t make any sense (and was incredibly annoying after the 100th time) but was a useful way of helping students to play with the sounds in words. You take a student’s name and put it through a formula that goes like this:

| Narissa | Shirl |

| Narissa, Fa-nissa Me Mi Ma-nissa Be Bi Ba-nissa Na-ri-ssa. |

Shirl Fa-nirl Me Mi Ma-nirl Be Bi Ba-nirl Shirl |

This or that?

Hold up two pictures (or show two pictures on a PowerPoint slide) and ask students which picture starts with the target sound. E.g. When focusing on the sound /f/ you could show a picture of a fan and a dog and ask, “Which one starts with the sound /f/? Is it fan or is it dog?”

Tips:

- Remember the focus in on sounds rather than letters, so the question is, "which picture starts with the sound /f/?' rather than, 'which picture starts with the letter <f>?'

- It’s a good idea to use images that align with the sounds you’re teaching in your phonics instruction. E.g. If your phonics scope and sequence introduces the grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs) m, a, t, s, i and p in the first phase, then you would make both the example and the non-example in the images align to one of those sounds. This way you can reuse the same images multiple times.

- When you're first introducing the individual sounds, try to avoid using words that start with blends. E.g. When introducing the /f/ sound, try to avoid using images that start with <fr> and <fl> to better help students discriminate between the different sounds.

- Once your students have developed their capacity to identify initial phonemes, you could use this same activity with a focus on final phonemes: “Which word ends with the sound /g/? Is it fan or is it dog?"

Many researchers agree that phonemic awareness is an important pre-requisite for phonics instruction (Kilpatrick, 2016, Westwood, 2013, Ehri et al., 2001, National Reading Panel Report, 2000) saying it “it primes or ‘front loads’ later phonics instruction” (Mesmer, 2022). This is an important area of early literacy instruction and one that we need to continue to build our own knowledge on as teachers.

Do you have a favourite activity for building students' phonemic awareness? I'd love to hear about! Join the conversation on the Oz Lit Teacher Facebook group.

Related Blog Posts

- What Is Phonological Awareness And Why Does It Matter?

- Strategies For Emergent Readers: An Interview With Jennifer Serravallo

- Should You Use Decodable Texts?

References

-

Ehri, L., Nunes, S., Willows, D., Schuster, B., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z. and Shanahan, T., 2001. Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence From the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), pp.250-287.

-

Gillon, G., 2018. Phonological awareness: From research to practice, New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

-

Mesmer, H., 2022. Alphabetics for emerging learners. New York: Routledge.

-

Kilpatrick, D.A., 2016. Equipped for reading success: A comprehensive, step-by-step program for developing phoneme awareness and fluent word recognition, Syracuse, NY: Casey & Kirsch Publishers.

-

National Reading Panel, 2000. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientifi c research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

-

Schuele, M. and Boudreau, D., 2008. Phonological awareness intervention: Beyond the basics. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 39(1), pp.3-20.

-

Westwood, P.S., 2016. Reading and learning difficulties, Camberwell, Vic: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Sign up to our mailing list

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news, updates and resources from Oz Lit Teacher.

We'll even give you a copy of our mentor text list to say thanks for signing up.